The study of the history of non-Western societies – especially those that have ‘failed’ – may be one of the most valuable resources that we have to help guide us through the coming ‘time of difficulty’ that we seem to be heading for.

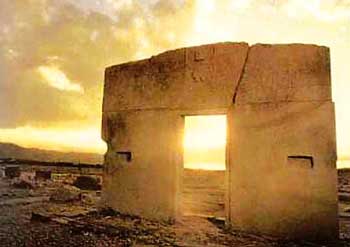

Watching a good BBC documentary about Tiwanaku, I was struck by how pertinent to our present climate change woes was the story of these people, not only surviving, but flourishing in an environment that most of us would consider adverse to human existence. Not only do they provide us possibly with lessons in sustainable living – with their numerous adaptive feats of agriculture, technology and infrastructure design, but, perhaps even more importantly, they are a ‘social experiment’ carried out across diverse cultural groups, and over a span of centuries, of varying landscapes and climactic zones. It can hardly be imagined that any projected environmental ‘study’ that we are capable of – however powerful the computers we might use to produce a simulation – could possibly come close to providing us with the real world information that just this one example can.

The pre-conquest cultures of South America (specifically the Andean regions, with extensions east into the Amazon basin, and west into the narrow strip of land that runs between the Andes and the Pacific Ocean) may seem remote and only of interest to eccentric antiquarians, but the topography of that continent has provided, throughout history, a multitude of incredibly diverse landscapes that challenged the survival of the societies who lived in them. The level of adaptation that these societies made (or were forced to make) to their environments have revealed the remarkable truth that, without fossil fuels, large domestic animals, the wheel, or any use of metals (and alloys) harder than copper, they managed, in many places, to sustain larger populations than we are capable of today, and did so with enough comfort to be able to produce monumental architecture. The very complexity of the topography of South America has created a multiplicity of ‘niches’, often abutting against each other, in which such societies could develop. Empires in this region could thus, even when not spanning vast distances, take in everything from a torrid seacoast niche, to the high Altiplano and everything in between. Of particular interest is that many of these ‘experiments’ ultimately failed when the climate changed.

There are countless other examples from elsewhere. The Maya for one, whose population in the relatively constrained Yucatan, in that relatively constrained space, may have reached the kind of numbers that the early Roman Empire reached in its encircling of the Mediterranean. The reasons given for the ultimate collapse of Mayan civilization are varied, but a favoured explanation is that this occurred as a result of environmental degradation produced by over population. Another example, perhaps the example, is that of Easter Island – a social experiment carried out on an island that, through its extreme isolation, was as closed a system as a petri dish.

Other civilizations experimented with forms of government and of economic organisation. The Achaemenid Persian Empire, for example (that I have been studying as the setting for a novel). The study of these ‘dead’ cultures may seem esoteric (for all their beauty and fascination): at times I have thought such to be a sort of ‘ancestor worship’ – but consider if these studies may not perhaps turn out to be critical to us as our own civilisation edges towards its own possible collapse from climate change, environmental degradation, and competing and failing models of governance?

As the West loses its pre-eminence in human affairs, we seem to be less and less blind to these other histories. Until recently we have been obsessed with ourselves, with tracing the rise of our greatness, so that so many of our historians have lavished their attention on investigating the ‘line of progress’ that has brought us – apparently – from the birth of civilisation in Mesopotamia, through ancient Greece and Israel (with an input from ancient Egypt), through Rome, to Europe and then the period of Western imperialism that has ‘blossomed’ into our current system of global capitalism. On one level, this could be seen as a sort of ‘psychotherapy’ of Western civilization, though on another could it not be seen as a neo-Darwinist project that has been developing a narrative for why our dominance was not only justified, but inevitable? Either way, it seems to me that as we (humanity) realize that our culture seems to be leading us to disaster, we no longer have the luxury of such self-obsession.

So, rather than considering this exploration of non-Western history as some kind of pursuit for ivory tower scholars, I would like to suggest that is in fact a bringing together of all the critical knowledge and wisdom that can be gleaned from the social experiments that humanity has been carrying out on this planet over thousands of years. These experiments, participated in by people like ourselves, pushed frontiers and called on the ingenuity that we are capable of and came up with solutions that it would be wise of us to take heed of. Even more, the failures of these experiments provide us with lessons that were bought with the lives and diminishing opportunites of people for whom their societies were not experiments, but the lives they lived as best they could.