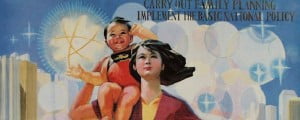

China’s One Child Policy

Much of the reaction to the recent change in China’s ‘one child policy’ seemed to focus on human rights: specifically the right of a woman to have as many children as she wants. A woman’s control of her own fertility has been dearly bought – for most of history women’s bodies have been controlled by men. In many places today they still are. Nevertheless, it seems to me that this issue has another side that needs to be expressed: our need to control our population.

We know that we are facing many worsening global problems: climate change, ecological degradation, species extinction, soil depletion, a diminishing availability of fresh water. Related to these is our ongoing struggle to feed ourselves, to provide a decent standard of living for people, medical care, education and general life opportunities. These challenges are directly related to how many of us there are now, and how many of us there will be in the future.

We also know that the rate of increase in our population is slowing. Some reasons given for this are decreasing infant mortality, the education of women and the availability of contraception. Given an improved standard of living, people choose to have fewer children.

Nevertheless, our population continues to grow and even the most optimistic forecasts suggest that a peak of something like 9 billion may be reached around the middle of this century, and thereafter, all other circumstances being favourable, our numbers will begin to come down. There are good reasons for supposing that circumstances may be anything but favourable. Even if they are, it seems inevitable that the ecosystems of our planet, and the other creatures that we share them with, are going to be badly damaged. It seems that we are unable or unwilling to make the changes that are necessary to ameliorate the worst of that damage.

It is in this context that I feel that we should be appraising the Chinese one child policy. For all the infelicities that have attended its implementation, the estimate for how many fewer people there are in China today is in the order of 400 million. Consider that, during the Chinese economic ‘miracle’, it has been calculated that perhaps 500 million people have been lifted out of poverty. These two figures are strikingly close to each other. In Africa, various countries that have increased their GDP dramatically over the past decades, have not seen a rise in the standard of living of their people because their populations increased so as to leave the average income much as it was before.

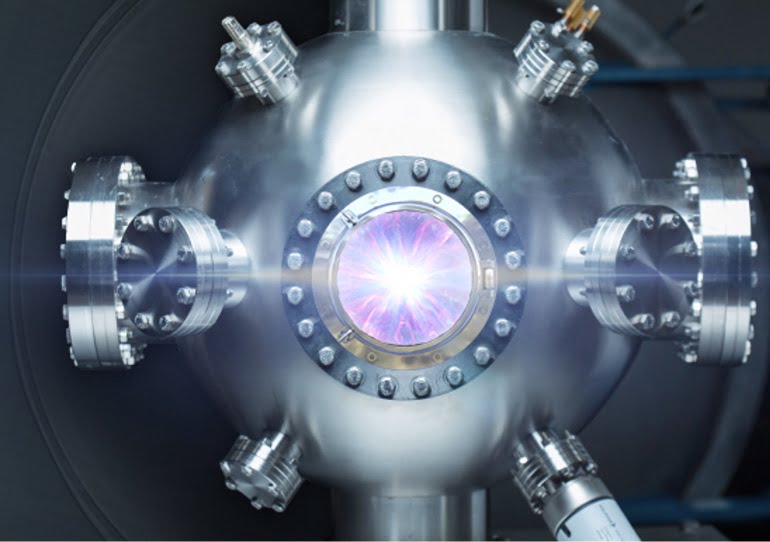

The Chinese authorities have said that they have relaxed their one child policy in response to the increasing imbalance there is in China between the old and the young. Taken together with the apparent lack of desire that the Chinese now have for big families, I find it hard to believe that what is going on is anything other than the result of careful planning. It seems to me unlikely that the Chinese planners in 1979 did not forsee that their one child policy would result in the age imbalance that we see today in China. Is it hard to imagine that they judged that, if they kept the policy in place for two generations, they would change the traditional desire for a large family, by showing their people through lived experience how much better their lives would be with fewer children to feed and educate? That this may have come at the cost of skewing the age profile was perhaps a price they were prepared to pay. Exchanging the certainty of disaster – let us not forget that China had a famine well within living memory and that they feed 19% of the world’s population with only 8% of the world’s arable land – for a problem that after all is one that they share with us here in Europe. A problem that, because of recent developments in technology, we are in a better place to deal with than we have ever been.

Given the magnitude of the risks we face, we may no longer have the luxury of having all the freedoms we may desire. Chief among these may be the right to have as many children as we want. Though we must do everything we can to protect a woman’s rights over her own body, we must also protect the human rights and life chances of children alive today, and of those yet to be born.

edited by a friend who prefers to stay anonymous