crucifix versus cross

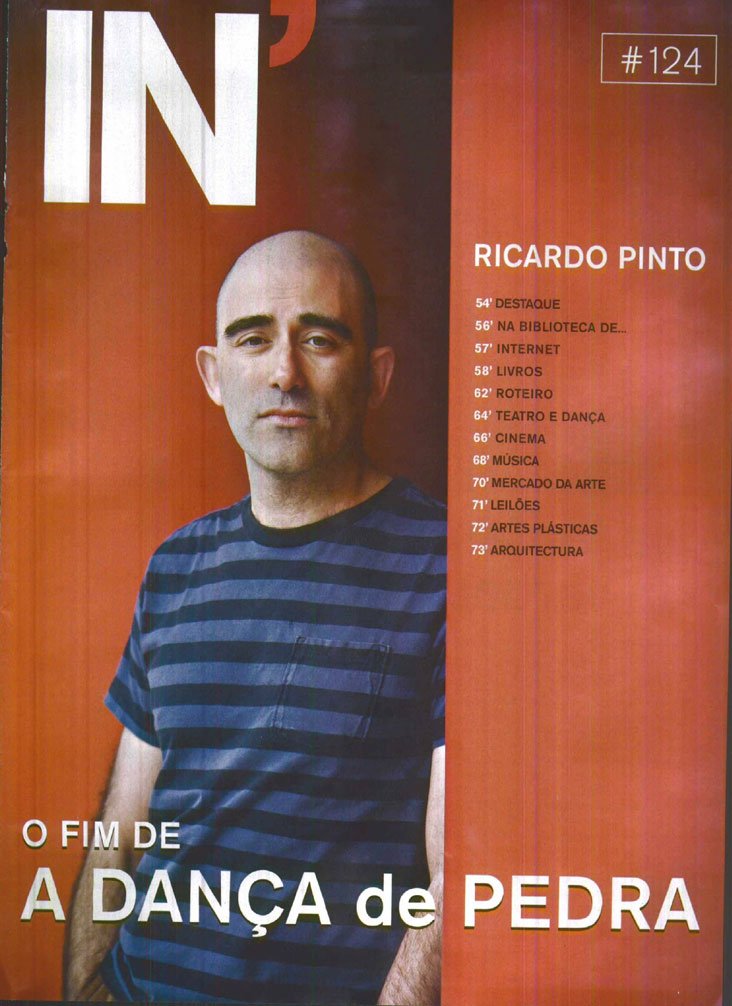

When I was in Portugal earlier this year, it occurred to me that not a single one of my Portuguese readers has ever mentioned the violence inherent in the Stone Dance, never mind complained about it. This stands in stark contrast with reactions in the English speaking world – where the violence contained in the books is often mentioned. This contrast linked in my mind with a comment my therapist once made to me that “you imbibed Catholicism with your mother’s milk”… At the time I was taken by surprise, being that I am an atheist and that I do not recall even being in a Catholic church (though I was baptised in one). My mother is a devout Christian, but though she was brought up Catholic, when we moved to Scotland, she abandoned Catholicism because she was uninterested in the schisms in Christianity. Her attitude seems to be that she believes in Christ and can’t see the point in denominations. As it happened, she walked down the street and joined the first church that she came to. As this turned out to be the Church of Scotland, she nominally is now a Protestant – though, as I’ve said, she’s not interested in such distinctions.

What, you may be wondering, does this have to do with the Stone Dance. Well, when I was in therapy, I became aware that the Stone Dance has a layer of structure that is profoundly Catholic in its sensibility. In fact, Catholic themes of suffering and redemption run through the books; there are fundamental subversions of the Garden of Eden story, of original sin, of the casting out of Satan from Heaven… All this in spite of me being an atheist and having been brought up with only a moderate smattering of Christian influence… But we can none of us, it seems, be free of what we “imbibe with our mother’s milk”…(see the first epigraph of The Third God)

What then does this have to do with how different cultures react to the violence in the Stone Dance… First: I myself was not really aware of the violence in the books as being an issue – violence seems to be such a natural part of our lives, that for people to take exception to it, seemed to me a tad perverse. I was, after all, writing a book about the world as I see it… and who can claim that that world is not saturated with violence? I began to see that it might not be the violence per se that some people were finding difficult, but rather something about the way that that violence was being portrayed. Please understand that I am here feeling a way through the shadows – I don’t claim to fully understand this – but I now wonder if it could possibly be accidental that the only other group of people who have not noticed the difficulty in this violence should happen to be people from the country in which I was born; that though I was only in Portugal for 8 years of my life… that I am still Portuguese. And what then could it be about being Portuguese that leads to a different attitude towards violence?

My solution, a solution that came to me when I was in Portugal on my recent visit, I can best explain by what I see as a distinction between the crucifix and the cross. In my experience, the dominant symbol in the English speaking world is the bare cross, unadorned, abstract. In Portugal, in the Catholic world in general, this cross has a man suffering on it. How profoundly is a culture shaped, the minds of its children shaped, by the difference between these symbols? The contrast between the abstract instrument of torture and execution, and the instrument being demonstrated in use, viscerally, by having a man depicted on it suffering? And it seems to me that the profound mystery (in the religious sense) here is that a man suffering on a cross should be thrust into the face of people – especially children – as the symbol of the most profound love. This seems to me to provide some insight into the difference in how people react to the violence in the Stone Dance. For that violence is ultimately about sacrifice and redemption. And it seems that I am Catholic enough to have portrayed a unity between violence and redemption, between violence and love, that is immediately understood by people who have grown up with the crucifix and causes much more of a problem for those who have grown up with the plain, bare cross.