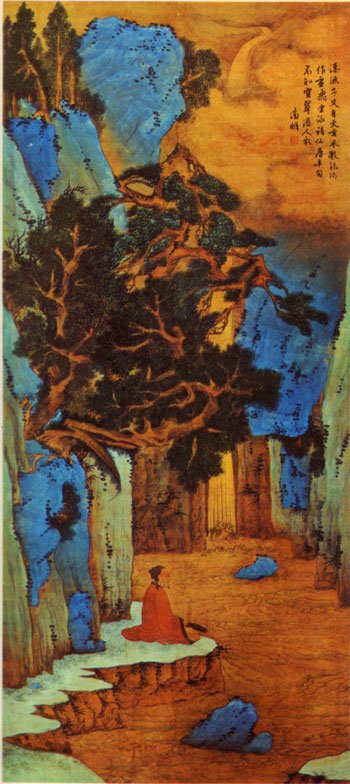

Having emerged in recent years from gestalt therapy, the Stone Dance (my own copyrighted version of auto-therapy *grin*) and a general focus on the internal world of the psyche (thus much interest in Jung) – all pursuits that favour subconscious over conscious, intuition over cognition, I have found myself becoming increasingly interested in looking outwards (as far indeed as the Universe) towards science and mathematics. No doubt this is part of some process of achieving balance between the outer world of light and logic and the inner world that is hidden in mythic shadow. The book I am going to talk about here might be seen by some as a rather extreme swing ‘the other way’ – but if so it seems to me the application of the T’ai Chi precept that if you want to move right, first move left; if left, first move right.

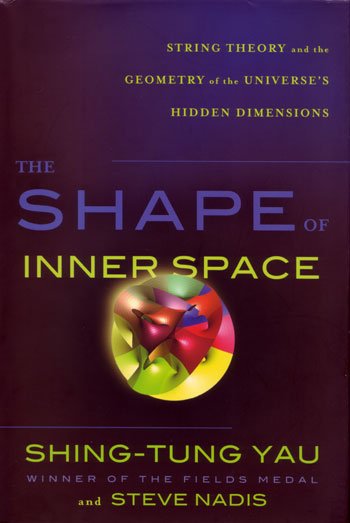

Now a book about string theory might appear at first to be only of interest to those of a rather esoteric turn of mind. That Shing-Tung Yau’s book seeks to explain this theory through mathematics might have you on the verge of surfing off to a more reasonable webpage, beginning a scream or simply fainting away with the sheer terror of such a thought. Please do none of these things, but give me a chance to explain.

The Shape of Inner Space is a truly remarkable book. It seeks to explain perhaps one of the most subtle and complex adventures that the human mind has ever attempted. It explains the way in which mathematicians, exploring abstract worlds of many dimensions, have seduced physicists with a vision of a solution to the rather thorny problem of how to reconcile two theories, both deliriously successful: Einstein’s General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics. Each of these theories beautifully describe, respectively, what we observe of the very large (planets, galaxies), and the very small (atoms and sub-atomic particles)… The bizarre thing, the thorny problem, is that there seems to be no way to reconcile the two. And yet, there must be some way… because these two worlds: the very large and the very small, clearly must form a single continuous world…

Some twenty years ago, Yau discovered a geometry, a ‘shape’ (really a family of very closely related shapes) that is called a Calabi-Yau Manifold. This shape exists in 6 dimensions. Mathematicians regularly explore geometries of any number of dimensions – what makes this one different is that it is claimed that it ‘actually’ exists. In an argument that for me recalls the maddest and most eccentric theological discussions of the ‘how many angels can dance on the head of a pin’ variety, Yau and his maths confederates came up with a solution to the ‘thorny problem’ that requires 10 dimensions: the 3 of space and 1 of time we live in and another 6. Where, may you ask, are these mysterious 6? Well, of course, since we can’t see them, they must be somehow hidden. In fact they must be so small, so tightly bound, that they are actually VASTLY smaller than the radius of an electron. These extra 6 dimensions, ladies and gentlemen, form an exquisite convolution of the most infinitesimal size that is some flavour of Calabi-Yau manifold.

So far, so crazy. It gets crazier. It is inconceivable that we could ever find a way of actually directly perceiving these tiny hidden realms. And yet, as you read this book, and you glimpse (for only delving directly into the fiendishly complex mathematics could you hope to ‘see’) the strange and bizarre landscapes described, you begin to see how one theorem is strung together with another, when you begin to get some understanding of the interplay of maths and physics, of the interactions between the practitioners of one and the high priests of the other – an astounding picture begins to form in your mind of this most breathtaking of ventures. Nothing less than an understanding of the universe.

What also comes across is how desperately ambitious this venture is. Even if at every point in our spacetime a Calabi-Yau is attached – and it may not be this kind of manifold – it could be something more ‘complex’ – there are, apparently, 10 120 (that is 10 followed by 120 zeroes) possible Calabi-Yau – each incredibly complex – so how do we find out which one describes our universe uniquely?

Ok, enough rabid enthusiasm. I can’t hope to explain here what I’ve gleaned by reading this book. What remains to do is to encourage you to read it. I won’t pretend to you that I fully understood what was going on all the time. However, Yau is aided by Steve Nadis, a brilliant science writer. Together they make great efforts to explain what is going on in ways that a reasonably intelligent person can cope with. Throughout there are many excellent diagrams and examples are given that really help clarify things. What is perhaps most important is that Yau comes at this from the point of view of a geometer. That means that he is constantly focusing on ‘visualizing’ the maths. Focusing on this topological approach certainly worked for me.

Most importantly, I read this book with my mind slightly out of focus – that is, not ‘clinging’ to the text too hard – if there is something you don’t grasp – reread it – if it still doesn’t ‘go in’ – just move on. I don’t think it’s the details that matter here, but the general drift of the argument.

Perhaps I’ve lost my marbles in trying to encourage you to read this book. Of course it’s a difficult thing to attempt. On the other hand it is trying to give you an insight into perhaps one of the most complex and bizarre ventures humanity has thus far attempted. Ultimately, I found it simply the most exhilarating trip imaginable.