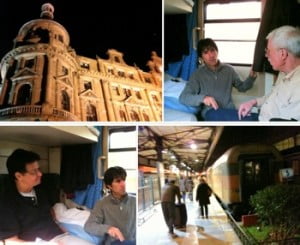

in Yazd

I wrote this on the 9th, but it’s taken me a few days to insert the photographs…

Before I talk about Yazd, I want to tell you what happened today. I had, with pleasing efficiency, got up early, had a quick breakfast and had managed to see one last garden, as well as breezing through a museum on qanats (more about that later). A last minute rush to change some money, quick packing, ordering a taxi to take me to my bus for Esfahan, and then checking out. Then the hotel receptionists informed me that they didn’t have my passport. (You have to hand it in at any hotel you stay at here.) They explained that they had accidentally given it to some Iranian woman in error – because our names were so similar, apparently… *crazed stare to camera* Quite.

I naturally displayed some anger – I chose not rein this in so as to make sure, across the language barrier, that they understood that I was REALLY not pleased. Apart from anything else, tourists have been arrested for not having a valid visa, never mind no passport at all! Their proposal was that I should go on to Esfahan as planned, and that they would make sure that my passport would be sent on to my hotel there, from Tehran – where, apparently, it is currently holidaying without me.

Needless to say, I was having none of this. I asked them: and what if the passport doesn’t turn up in Esfahan? What would I do 150km away when the authorities asked me for my papers and I said, in my fanciest foreign: oh, alas, my last hotel in Yazd gave it away mistaking some Iranian woman for a bald farangi (oh, yes, that is what all non-Iranians are referred to as – have I said this before?). Tolerant as I am, and understanding, I’m not sure that were I in their position, I would find this entirely convincing.

At this my time of need, the estimable Mr Lorian (of whom much more later) appeared as the taxi driver who the hotel had phoned to take me to the bus terminal. Thinking about it now, this appearance at convenient moments of familiar characters might make me suspect that I may be in some kind of Persian farce – however elegant with its adobe walls, wind towers and formal gardens. I told them I wasn’t budging and they, bending over backwards in what I felt was true embarrassment and contrition, told me that I could stay at their expense. Indeed, I am typing this to you from behind the reception desk where they’re letting me use the only computer in this hotel with an internet connection. All food etc would be gratis. Somewhat appeased, I retired to lick my wounds.

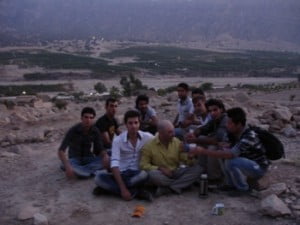

Later, taking advantage of my snowy carte blanche, I joined the impossibly crazy seminar of local businessmen (perhaps not so local, my various frantic taxi rides this morning have all fallen foul of the large and posh white cars ferrying these luminaries to this hotel – located as it is within the warren of mudbrick alleys of this exquisite city.) Now I was about to tuck into the feast they had laid on for these gentlemen, sitting cross-legged amongst them on one of these takhts rather natty raised platforms, or ‘day beds’, when one of them, tripping, deposited an entire plate of food on my leg and jacket. More hotel staff appeared, fussing, and the hotel has now agreed to wash those clothes, and all the other dirty ones I have been lugging around with me in search of a laundry. I’m beginning to feel that I have somehow wandered on to the set of a Charlie Chaplin film – in which I am most definitely the tramp… What can I do but play my part and hope that my passport returns and that I can move on…

To more interesting matters: Yazd, oh Yazd! How lovely she is lying here between two vast deserts. I have really fallen in love with her. Bizarrely, this is the one place where I’ve developed yearnings to have a house – not seriously – but still… It is cold here – very cold, especially once the sun goes down. I came to Iran without a jumper and now that my coat is in the wash, I have asked to borrow one – we shall see how this further enhances my comic role. Checking out the temperature in Tehran and Shiraz before I left – if not scorching, at least warm – I assumed that this would be true for the whole country.

Another climactic digression, if I may. On reflection, I don’t think that, in my last post, I properly managed to explain the climate here. Iran is a very complex landform – one far more complex than most of us are used to. I say this with some confidence because this is a landform I have spent some time meditating on while peering at maps and climate charts. In spite of this I simply didn’t get it. To try and put it as plainly as I can: each city here – certainly the ones I’ve visited (though my endless interrogations of the natives seems to suggest that these are not anomalies) – each city here lies at a unique confluence of terrain, aspect, height and position relative to bodies of water, mountain ranges, seas. As a consequence, each city (and it’s environs) has a wholly unique climactic character. When this is combined with the overlaying of different migrational genetic groups, cultures, languages etc etc – it means that each city is unlike another.

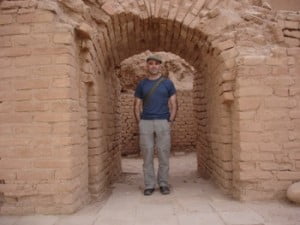

Yazd is at the moment, as I have said, cold. But everywhere I go there are groves of pomegrantes with overripe fruit fallen and split into red grimaces on the dusty earth. The city, the old city – for what interest is there in the hideous urban sprawl that spreads here beyond the ancient centre, as it does around every city I have been to in Iran; with it’s lookalike concrete monstrosities, the hideous air conditioners clinging above windows like ticks, and all subject to the merciless tyranny of the petrol engine? The old city is a soft flowing brown surface, pierced by all manner of tunnels and openings, of arches and towers, of wind towers… oh the wind towers. Much of it forms a roofed over network – elegantly arched and vaulted where lined with shops and the workshops of artisans, beating out metal trays or selling fruit and vegetables, or hills of shelled nuts and dried fruits on great steel platters. To put it bluntly, the topography of Yazd suggests that its inhabitants – the, as always, delightful Persians; that much at least seems to be invariant across this land – seem to have a need here to live like termites. Suggestive this of the scorching – well above 50 degrees celsius – that characterizes the long summer (thankfully with zero humidity). I have experienced nothing of this directly, but I have seen so many, many signs – for this is the great joy of the ancient Persian city: that it is exquisitely moulded to its particular climate – in ways that all the planet, it seems to me, needs to learn from.

I came here from Shiraz after Karim put me on the bus. I was sitting just behind the driver, and he insisted on me coming down to sit on a seat that folded down across the bus doorway – and gave me tea and more of those damned addictive roasted and salted pumpkin seeds. I may be beginning to get the hang of these: you nibble along its length like a mouse, then insinuate the, hopefully, uncrushed kernel onto your tongue, while discarding the rest. The first time I was given these (no doubt you have eaten them often and are considering me tres gauche) I munched the whole lot – crunch, crunch, crunch, scratchy swallow – much to the amusement of the driver who gave them to me.

When I arrived for some strange reason no taxi was prepared to take me into the centre. A kind man, drew me into a taxi with him. We both got out somewhere or other, and he welcomed me warmly to Iran, got my email address, and then hailed me a taxi and insisted on giving the driver the money for it. Quite, quite typical behaviour, of course.

I was whisked away to the hotel I had chosen from my guidebook, and found that it lay down one of these covered bazaar streets, at the end of a narrow alley. This hotel, a typical old house, is built around a great court roofed with canvas. So far, so good. I was less enamoured of the ‘bathroom in a cupboard’ – when I took a shower, the water was just pouring down the inside of the old wooden door. In truth – and I’ve commented on this before – Iranian plumbing is a bit eccentric. I’ve only twice come across a shower curtain. Mostly, the shower is merely set up on the wall of the bathroom and when you shower, the entire bathroom gets soaked. Nor did I like sleeping in a room without any window anywhere… nor, for that matter, the rather fabulously expensive buffet I had that night. So, the next morning, I defected to another hotel – even grander with a larger courtyard (I discovered two more today), and roofed by something like a rather glamorous circus top and, though a bit more expensive, I was given a nice large room with windows overlooking the court.

On a whim, one morning, I phoned a tour guide whose name was in my guidebook as being a Zoroastrian who had the ‘in’ on the rather sizable Zoroastrian community – largest, I think in Iran – and rather a sad remnant considering that, before the Islamic conquest, the whole country followed that faith. I shall not lecture you on Zoroaster, I’m sure you will piece it together from what follows. The man appeared, Keykhosro Lorian – he told me that some time in the past, people were asked to choose family names, and so they did so, with some degree of randomness. He appeared, and it was immediately obvious that he was the guide for me. When I opened with my well used: chand toman? (how many tomans), he countered with: you say. I made an offer, he laughed… and after some negotiations, we settled on a price.

Off we drove, first along streets where he asked me to tell him which houses were Zoroastrian and which Muslim. I did my best – and I did get one thing right: that some doors had two knockers – one for women callers, the other for men, that by producing a different sound, alert the inhabitants of the house to send an appropriate person to answer the door. Clearly Muslim then. The Zoroastrian houses – some having but a single knocker – though not always so, rendering that Holmesian tool in my kitbag somewhat dodgy – had wet marks outside the door because, each morning, water is supposed to be thrown out – I never did get to the bottom of why. Then there was the possibility of a cypress tree somewhere in the vicinity. Thin pickings, I think you will agree.

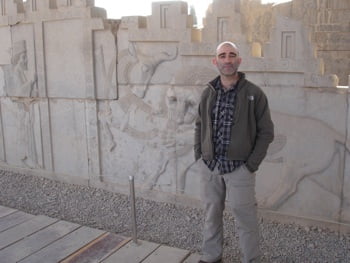

After that, as Mr Lorian and I continued on our way to the fire temple, the inquisition continued. Whenever I would get something right he would bark: Bravo! Within the building, through a pane of glass, I observed an enormous ‘goblet’ in which burned a cheery fire. The same fire that has been burning continuously for some 1500 years (something of that order). Not at this place exactly, but lit from another somewhere else, and generally emanating, by direct ‘descent’ from an ancient fire. This is all a lot deeper than it might seem – they do not worship the fire, it is merely a symbol of their one and invisible god. And, as I think I have already mentioned in another post, we owe to the Zoroastrians all manner of spiritual inheritances: the Last Judgement, angels, the Devil, the Holy Spirit, the notion of Heaven etc. Such a profound legacy, indeed, that it only makes it sadder that the number of Zoroastrians in the world number perhaps 150,000, these mostly in Mumbai (I think), with only a community of 12,000 in Iran, according to Mr Lorian, who is very sad about it. His community is dissolving, through intermarriage, through migration – many Iranian Zoroastrians having moved to the US and Canada – and his single daughter, Nirdal (I may have misremembered this – though it means “evening star” – ie. Venus – Zoroastrians names all being derived somehow from nature), 11 years old, is already being seduced by the American visions of consumer bliss she watches on her friends’ satellite TVs. He worries for her future and that of his culture, whose core tenets are threefold: good thoughts, good speech and good acts. You can’t argue with that, now can you?

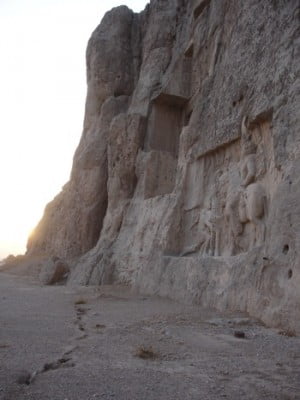

Next we drove out of town to two massive rings high on hills – the famous ‘Towers of Silence’. Here, until perhaps 50 years ago, Mr Lorian’s community would carry up their dead. Carefully washed, they were left there for the vultures. In a few days they would return to find the bones picked clean. These would then be desposited in a central well. I climbed to the tallest of the two. It is mostly ruined now – a ragged hole with the remains of a stone pavement around it upon which the bodies were laid. These towers are 400 years old, but there are others far older. They used to be way out of town but, gradually, the Muslim housing crept closer and closer to the towers, until the elders of the Zoroastrian community decided it was better to desist from a practice their neighbours neither liked nor understood. Now, still fearing to pollute the earth with their decaying dead, they bury them in concrete lined holes.

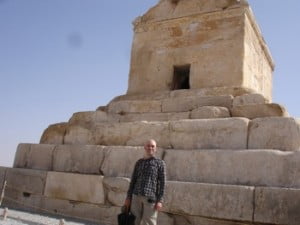

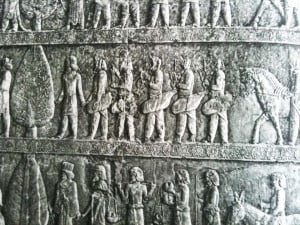

Zoroastrians venerate water, earth, wind and fire and they strive to keep these undefiled. They could neither burn, nor simply bury their dead – for a corpse is impure. A Zoroastrian would not even wash or urinate in a stream. It is interesting to wonder if, were the country still Zoroastrian, there would be so much litter lining every road through the glorious uninhabited spaces, or clogging streams and rivers whose purity of taste is delicious – I’ve certainly never tasted water comparable (though I was thirsty). Incidentally, Cyrus would only drink water from the river that flowed past Susa, water from which was carried around after him, wherever he went, in silver containers, a practice carried on by all the Achaemenid kings – most of whom – Cyrus possibly too – were Zoroastrians.

One of the hotel receptionists keeps answering the phone beside me and deploys, as some women here do, an unnaturally high voice. This is something I’ve also noticed among Japanese ladies and in Japan, if the samurai film is to be believed, the men used to growl their words like grumpy bears. I do wonder if there is some kind of cultural trope operating here in Asia where people exagerrate their gender through their voices…

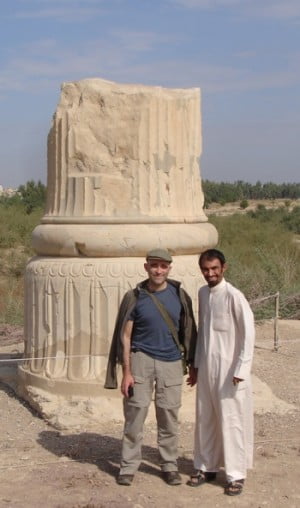

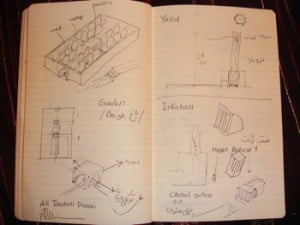

Meanwhile, back in reality, Mr Lorian next drove me to Mebod, another ancient town hereabouts, where I explored a vast ‘pigeon tower’ that had nesting niches for 4000 of our feathery brethren. What was this used for? asked Mr Lorian. For food, I said, and he shook his head smiling: Persians don’t eat pigeon. Their eggs, I offered, smugly. Nay, his head said with another shake. Fertilizer! I said. Bravo! he beamed. There had once been 1600 of these towers around Yazd, all of them producing guano (that was once the chief export of Peru). Next was an ‘ice house’ – though to call it that is to reduce something sublime to banality. Yakh Dan – the first being pronounced in the Scottish as ‘yach’. (Incidentally, the Persian terms for many things here lose a lot in the translation. ‘Tower of silence’ is actually ‘dod gaa’ – Judgement Time – and the modern cemetries are called, by the Zoroastrians, Areh Gaa – ‘Silent Time’. Wind towers are ‘bad gir’ – literally ‘wind grabbers’). Back to the ice house. Under a great adobe dome, lay a deep, smooth pit into which, down its wall, curved steps. The whole thing, once my eyes adjusted to the gloom, looked like an Anish Kapoor sculpture. The way it worked was thus: outside in the open, they poured water into shallow troughs and built walls around these to keep them in the shade. At night, in winter, when it got cold enough, the water froze. It was cut into blocks, put in the ice house bowl, each layer covered with straw. Thus a large supply of ice was available during torrid summer days. Genius!

Incidentally, when I asked Mr Lorian whether his community would ever return to ‘sky-burials’ – he waved his arm at the sky and I understood: there are no vultures. Specfically, if the functioning towers of silence in India are anything to go by, griphon vultures. Recently, in India, some antiobiotic they have been giving the cattle has decimated the griphon vulture population – poisoned by feeding on the carcasses. Consequently, communities near the towers of silence there have been dismayed to find bits of granny being dropped on the streets by the far less fussy eaters that are the vultures who have taken up the job.

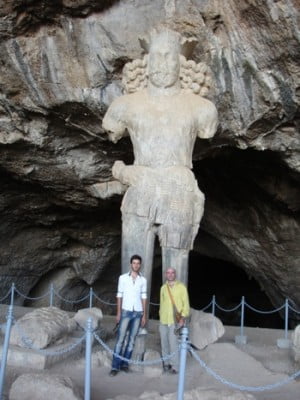

After lunch, Mr Lorian and I drove off across the desert towards another gorgeous range of violet mountains. Deep in among these we climbed to a narrow valley and parked beneath some rather 60s looking platforms stacked like bracket fungus up the cliff. Climbing to the very topmost of these we reached a curious shrine, holy to Zoroastrians, called Chak Chak – literally: Drip Drip. And, indeed, inside the shrine, the air reverberated to great drops of water falling from the overhanging rock into bowls – as has been happening for hundreds of years. Indeed it is strange in this arid landscape to find this inexhaustible supply of water so far above the water table. There is a story of a Sassanian (who were all Zoroastrians) princess fleeing into the desert from the Arab invaders and miraculously calling into being this water; another story claims these are her tears.

The complex has been built by Zoroastrian pilgrims for celebrating a four day festival every June. The ambience of the place, and the way Mr Lorian described the making and sharing of food, and the sleeping on the platforms gazing up at the milky way, made me imagine something funky like Woodstock. The view was certainly stunning, the air fresh (and free of petrol fumes) and there were wizened old fig trees, eucalyptus and wild pepper.

Dusk thickened as we reached the abandoned village of Kharanaq – abandoned, yes, the villagers have moved to a modern town, but daily pass through their old village, all of adobe like melting chocolate, to their fields in the valley below. Two of these villagers were sorting and washing yellow carrots (a small bunch of which I have in my rucksack for later munching). A spooky place, and beautiful.

This business of adobe – or mud bricks covered with a plaster of mud strengthened with straw (rather the same principle, it seems to me, as steel reinforced concrete). Close up it is like smooth and curving chipboard – with more emphasis on the smooth and less on the chipboard *grin* An amazingly versatile material that I have had a tendency to disdain – being somewhat obsessed (as I imagine most Europeans are) with stone. Indeed, in our rainy climates, adobe would quickly sag. My understanding is that the Potala Palace of the Dalai Lamas in Llhasa is made of adobe – and has to be repaired after heavy rain. Mud brick construction has been the basis of many civilzations – not least Mesopotamia – and now that I’ve seen it up close, I have come to realize that it is really rather wonderful. Not only can you build massive structures, and delicate ones – no doubt rather quickly – but it is also an excellent insulator – keeping buildings warm in winter and cool in summer – and, of course, it is ecologically very, VERY sustainable. In comparison to the hideous carbon dioxide excesses of producing concrete, it only takes some earth, water and sun to bake it.

Let’s talk sustainable architecture. Ok, I’ve already burbled on about ice houses and adobe. I would like to add two extra elements: wind towers and qanats.

Qanats – long a passion of mine – originated probably in eastern Iran – perhaps western Afghanistan. (I have a feeling that I may have gone on about this before – if so, please bear with me – and, after all, it would hardly be an obsession if I didn’t go on and on about it whenever the opportunity presented itself!) To build a qanat you must first locate a source of water in some high ground – the ubiquitous mountains of Iran hove into view – and then to construct a channel to lower ground where you have your settlement already, or where you wish to build one. This channel of water turns your lowland site effectively into an oasis. Now with the kind of heat we have around here (and, let’s face it, there’s not much point in going to all this effort if you have abundant supplies of water falling from the sky – and so we’re naturally talking about dry and hot places), with this heat, a channel running along the surface would lose most, if not all, of its water through evaporation. The solution is to put your channel underground – no mean feat, you’re thinking. No. And, though the qanat builders cunningly effect their underground channel to be almost horizontal along its course, the gentle flow still erodes the earth tunnel you’ve built and so you need to sink ‘wells’ all along its length, to get down to it to dig it in the first instance, and to repair it as an ongoing concern. Thus you end up with something that looks like the holes in a flute running down the slope of the mountain to your settlement. What you also end up with is a spring wherever you want it, daily pumping out delicious and cool mountain water into your houses and gardens and fields. More genius!

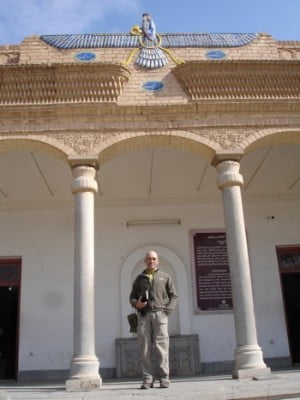

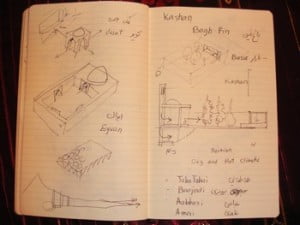

Wind towers, or ‘wind grabbers’, are tall structures – I think mostly of adobe – that rise up from buildings and present openings to the prevailing breezes. This cooler air is further cooled by being encouraged to pass over water. The conduits sometime have kinks in them holding shelves that collect dust and sand. What you end up with is a constant flow of cool air. I stood beneath one today, in the Bagh-e Dolat Abad, the tallest wind tower in Iran at 33m. A delicious, fragrant stream of air simply wafting down from the sky. Perfection!

So we have our cheap, sustainable building material, adobe, an unpumped water supply and a natural air conditioner without all that nasty drying and rattling – and these are, above all else, passive technologies!! These systems, all tuned to local conditions, with the addition of building shapes that reduce the amount of a building that at any time receives direct sun – are all passive. Silent, using no energy – could anything be more important, to a world in which we need to wean ourselves off fossil fuels and a general excessive use of energy, than this way of thinking?

While driving through a ruined Zoroastrian village, Mr Lorian pointed out a couple of dogs wandering around where there was no longer any water, not anything to eat. He pointed out that Zoroastrians greatly value dogs – often giving them some of any cooked food before people eat. This stands in direct contrast to Muslims who apparently despise dogs, considering them filthy. I’ve been wandering around Muslim Iran showing photos of my family – because that’s what they want to see – and of my poor, ancient little pooch. Little did I know that I may as well have be en showing them photos of my pet cockroach.

Yazd is however awash with cats. In one of the hotels, when I sat on a divan eating my dinner, there was one particular tabby with one eye who stared me out until I gave him something.

Last night, after 11:00pm, there was a knock on my door and, most apologetically, one of the hotel staff handed me my passport that one of them had gone to the airport to fetch for me. So I have lost a day in Esfahan, but it could have been worse.