why do electorates divide nearly 50:50?

Have you ever wondered why so many recent political votes divide their electorate almost 50:50? This is my attempt at a simple—perhaps obvious—explanation.

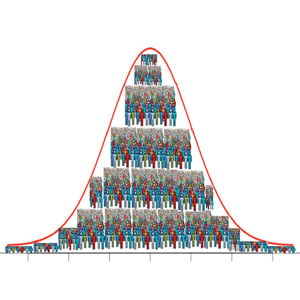

The results of the referendum for Scottish Independence (No 55.3%: Yes 44.7%) and the Brexit Referendum in the UK (Leave 51.89%: Remain 48.11%) seem to me remarkably close—especially given that in one case you had 3.6 million people voting, and in the other 33.6 million. Why were these not 60:40, or even 80:20? What occurs to me is that, when you ask an electorate a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ question, they will naturally fall into a normal distribution—’yes’ on one end and ‘no’ on the other. If you pull from both ends, the distribution might tear nearly 50:50—people naturally tending towards the end of the distribution that they are already closer to.

The 2008 US presidential election (Obama 52.9%: McCain 45.7%) and the 2016 election (Trump 46.1%: Clinton 48.2%) are also remarkably close to being 50:50—and, in these cases, 129 million and 128.8 million people voted, respectively. With only two parties, the electorate of the USA will also naturally fall into a normal distribution, and we can apply the argument above.

Even in elections where there are more than two parties, the results still seem to follow this pattern. The 2015 UK General Election (Conservatives 36.9%: Liberal Democrats 15.1%: Labour 30.4%) and the 2017 General Election (Conservatives 42.4%: Liberal Democrats 7.4%: Labour 40%)—excluding a few percent for smaller parties—have the Liberal Democrats holding onto a bit of the centre of the normal distribution, and the rest moving to either end. That having more than one party does not make the distribution move into an extra dimension (so there would be three or more points of attraction), would seem to be because, politically, electorates are on a left/right spectrum, or open/closed, or even optimistic/pessimisti—and, so, again we can apply the argument above.

As an afterthought: I wonder if this is why so many political systems formulate themselves into having only two parties, or, indeed, if the normal distribution—using our oft-used argument—encourages the formation of two parties? Whatever the truth of that, a democracy with two parties can be confident that it will divide an electorate nearly 50:50—thus precluding the danger they may end up as a one party state. Perhaps this explains the mantra behind occupying the ‘centre ground’—after all, it is in the centre, where those few extra percentage points can be gained, where an election is won or lost.