LEGO and the digital mind

In a previous post, I argued that LEGO, when it consisted mostly of simple bricks, was a superior creative tool for a child than more modern LEGO with its complex pieces. I have come to a more nuanced conclusion: that though classical LEGO promotes one kind of creativity, it may do so at the expense of other kinds.

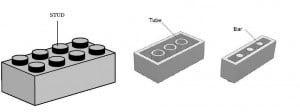

I still believe that simple, classical LEGO is an instantiation in the physical world of an aspect of human thinking that is located in the left brain hemisphere and that focuses on orthogonality and the counting numbers. Orthogonality is expressed in LEGO by the dominance of horizontals and verticals and right angles. The counting numbers are expressed by the studs on the upper surface of its bricks, and the tubes or bars on their undersides*. We can build structures that have width or length 1, 2, 3 studs etc, but not 2 and a bit. For this reason LEGO was used in my primary school as a way of learning basic arithmetic. Classical LEGO is essentially ‘digital’.

In a sense classical LEGO is a way to exercise this aspect of human thinking using our hands. I believe that this is not a one way process, that it feeds back into our minds and reinforces that way of thinking, perhaps even affecting brain structure.

I should have noticed this feedback effect when I stated in that previous post that LEGO has influenced the way that I ‘build’ texts. This is my lived experience, and suggests that LEGO has influenced the way my brain functions, or at least the system of conceptual metaphors that I use in my creative work. This effect is unlikely to be unique to me.

When I wrote that other post, a friend disagreed with my claim that modern LEGO was restrictive on the creativity of children. He told me that he had witnessed his children being freely creative with LEGO Technic. That niggled at me. I still believe that classical LEGO does enhance creativity, but specifically that kind of left brain processing that is obsessed with straight lines, horizontals, verticals, right angles and the counting numbers. Modern LEGO, by being less digital and more analog, may encourage a more freeform creativity that may even be beneficial to the development of a child’s brain.

Increasingly I suspect that our ‘digital revolution’ is something of a trap. Digital objects and processes are profoundly human; we find few right angles in the non-human world. As more and more of us live in man-made spaces and are mesmerised by digital objects, our exposure to and interaction with the analog geometries of the non-human world diminish. This leads inevitably to a diminishing awareness of the natural world from which we arose, and upon which we still rely in so many ways.

I began these musings by trying to express the superiority of classical LEGO over the forms it has evolved into. But as I strive to free myself from the tyranny of the right angle, I now wonder what part this children’s toy has played in that indoctrination. Considering how many children’s minds may have been at least partially formed by classical LEGO, is it fanciful to suppose that this had something to do with the advent of the digital revolution that occurred when they grew up?

*The bricks were also generally of a unit height, but this was somewhat diluted by the introduction of pieces a third of that height.

Afterthought

When I arrived in Dundee as a seven year old, I was playing with my LEGO on the floor of a hotel foyer. A woman knelt beside me who had just arrived from Hong Kong. She talked about the junks in the harbour there and offered to show me what one looked like. She began to build a junk with my LEGO, trying to capture the swell of its hull by connecting it at all kinds of angles, and without regard to the colours of the pieces, and leaving holes everywhere. I remember being outraged at this not being the proper way to build with LEGO. What really offended me was the lack of right angles.