giving up our first prize

Eating meat adjusts how we think about other animals, could that in turn carry over to how we treat each other? Meat eating is playing a part in the various ecological crises that we are intensifying. We became major predators when we first brought down a large animal and devoured it. A prey species, we have become the greatest predators of all. Is it time that we should give up being predators altogether?

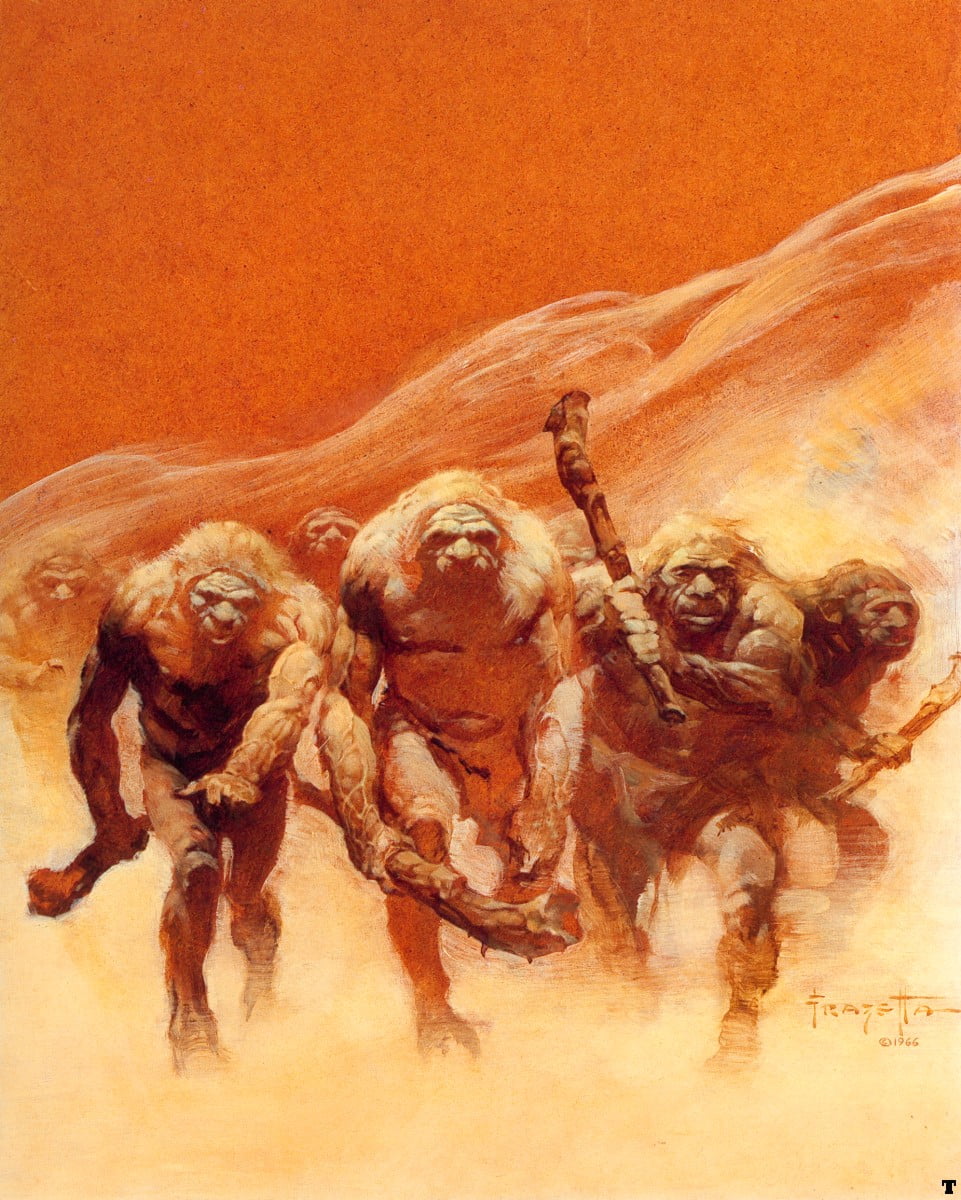

A lion takes his meat as his by right. Whatever doubt his species may once have had about its right to feast on meat, was lost way back somewhere in its descent from those tiny mammals that scurried at the feet of dinosaurs. By contrast, we still have most of our prey instincts intact. We are a recent predator descended from a long line of prey. Sure, like other apes, we sometimes fed on meat, but that would have been prey smaller than ourselves, and rarely. When we joined the wolves in being able to bring down animals far larger than ourselves, it was because, like them, we hunted in a pack, though we had to arm ourselves with the weapons that nature did not endow us with. This was and is our first and greatest prize. When we began to eye the crown of supreme predator. Now even lions fear us.

Prey become neurotic predators. We, the supreme predator, are afraid of the dark. The stories we tell our children are haunted by the barely concealed terror of being eaten alive. We have often taken on the guise of other predators – becoming Eagle and Jaguar Warriors, beserkers in bear skins; we have tried to associate ourselves with wolves, tigers, sharks – in the hope that something of their sleek and merciless ease with killing might rub off on us. Killing doesn’t come naturally to us. Once the killing of animals is not something that we grow up with, many of us become squeamish and reluctant predators. Even as we farm animals to be slaughtered for our plates, we tell ourselves, especially our children, sunny stories of smiling cows in green fields, of gambolling lambs on hillsides, and littly piggies who wear waistcoats and live in houses. We hide the slaughter, and increasingly eat only those cuts of meat that carry fewer hints of where they come from. Not for us the trotter, nor the boiled head. Not for us the lungs, the heart the brain. In school we are taught about our own lungs and heart and brain, and perhaps, seeing such organs on our plate, we smell cannibalism.

On another front, the march of science has consistently whittled away at the barrier between us and other animals. Once this barrier was absolute. We had been made in God’s image and the animals had been put on Earth for our use. Darwin fatally wounded that conceit. He forced us to accept what in our hearts must have always been obvious: that we are just another animal. It must have always been difficult not to notice that we shit as animals do, and have sex, that we die of disease as they do, and bleed as they do when we are cut. Yet still we have tried to cling to our otherness: we make tools, we have feelings, we make plans, we speak to each other. One study at a time, these supposed differences are melting away. Not only apes but crows make and use tools. Elephants and chickens communicate with a variety of calls. Elephants and dolphins can recognize themselves in mirrors. Jackdaws hide nuts from other jackdaws by employing a ‘theory of mind’ to understand what the other bird is seeing and thinking. We are in such confusion that serious attempts are being made to give our nearest cousins ‘human rights’. And once we let them in to sit beside us, how long will it be before we invite the next species, and the next?

It is hard for us to give up eating meat – it is entrenched at the heart of so many of our cultures. People everywhere, for whom meat has long been a rare treat, long to gorge on meat as a proof and demonstration that they have become rich. Yet, we are learning that our desire for meat is outgrowing the capacity of our planet to supply it.

It seems to me that there may be a deeper imperative to consider giving it up. So many of our problems seem tied up with our need to maintain our claim of being exceptional, special and unique. Is this not the basis on which we prioritise our wants over those of the other animals with whom we share our planet? And the primary commandment that enshrines this relationship is that we forbid animals to eat us, while we insist on our right to eat them. Not only to eat them, but to brutalise and diminish them in our factory systems. And as the barriers between us and them thin, so the barrier between a factory farm and a death camp thins. And I come back to this: how much does the way that we treat animals contribute to the way that we treat each other?

So, perhaps, it is time for us to give up that first prize. Becoming predators allowed us to become who we are. Becoming the supreme predator has long supported the vainglory that allows us, an animal with prey instincts, to kill and maim, to mistreat and treat as objects not only other animals but perhaps each other. Perhaps we will not stop mistreating each other until we stop mistreating animals. If we learn to treat them with compassion, how could this not help us to treat each other with compassion? Now, we have no reason to fear other animals. Let us stop making them have to fear us.

revised on 24th of November after a comment from John Robertson