on the Trans-Asia Express…

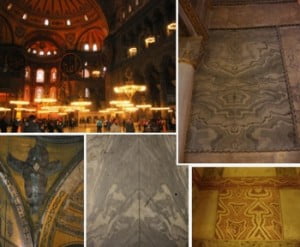

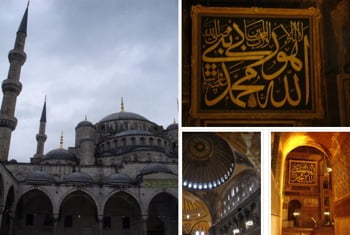

It was colder in Istanbul than in Scotland when I arrived, blustery and lashing rain. I spent the next day, my only day in the city, incredibly cold, but unable to return for an extra layer – I had not thought to bring warm clothes at all – because my rucksack was locked away in a cupboard in the hotel I had had to check out of. The Blue Mosque was closed for prayers – the beautiful chant of the muezzin drifting into the hotel had alerted me – against the message of the decor – that I was on the edge of Europe. Hagia Sophia, even ravaged, stood a gorgeous testament to the glory of Byzantium. Of course it’s dome and vast lofty space struck awe even into one jaded by the scale of modern cities. The Islamic calligraphy spoke eloquently of other glories. But for me, beyond the theatrical effect produced by the constellation of chandeliers just above our heads, it was the slabs of patterned marble forming panels in the wall, and especially paving the floor in a stone analog of marquetry symmetry, that most entranced me. This greatest of basilicas only served to convince me further how vulgar is the interior of St. Peter’s in Rome. Of course, today, with the place buzzing with tourists, it is nigh impossible to conjure up the place with its inner skin of golden mosaic intact, candle lit and filled with the exquisite harmonies of Orthodox singing – which miraculous vision caused the envoy of the Prince of Kiev to feel he was in heaven.

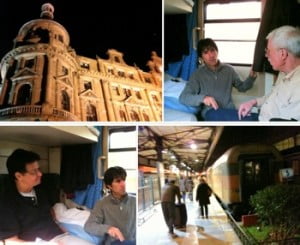

That evening I crossed from Europe into Asia, over the Bosphorus by ferry. Entering the looming excess of the Hydapasha station, that I was later told had been built by the kaiser, I boarded the Trans-Asian Express. Without thinking much about it, I had imagined that this might be something like the Orient Express – in romance if not actually luxury – but of course it turned out to be nothing of the kind.

I was quickly bundled out of the compartment that was the one printed on my ticket and into another one occupied by a retired German professor and two Iranians. They had already decided who was sleeping where and so I was told which of the two top fold down bunks was mine. These companions were quickly to become a sort of temporary family. In the little closed travelling world of the train, each cabin became a home, the corridor the street that linked them, and the dining car our public square. Rules that needed no explaining structured our social polity. Compartments became inviolate to anyone other than it’s occupants; who each had within it his place. Each carriage had a sitting toilet, a squatting one and a tiny cubicle with a small sink. Rituals of communal eating developed, courtesies of sharing, meetings in the dinning car that had the character of diplomatic and cultural exchanges where people made enquiries about geographic origins, negotiating which languages to use, with people who spoke more than one language automatically becoming willing interpreters. Sometimes, when trying to resolve for someone what food they wanted, chains of interpreters would translate, for example, from English in German, from German into Persian, from Persian into Turkish – and back the other way. Conversations and exchanges of information that were of interest to others were disseminated by the participants out along the language lines. On the second night this culminated in a party, in which, lubricated by beer, we had a sort of international ‘love in’. I had a particularly delightful conversation with Tolul, a young Turkish student from Izmir, about his country, politics, and the cultural and linguistic ties between Turkey and Iran.

Meanwhile I was getting Persian language lessons from Karim and Muchaba. They patiently answered my ‘how do you say…’ in Persian questions, and when I wrote down their answers in Persian characters they were kind enough to correct my spelling. One morning Mustaba burst in while I was still dozing, spouting a constant flood of Persian, and ignoring my cries of: ‘I don’t know what you’re saying!’ Later Joachim suggested that Muchaba had probably been praying *grin*

Joachim, at 70, is on another of the solo adventures that he only began once he retired from teaching. These have included a journey from Europe to China and Tibet by train. He told me that he is saving South America for when he will be too old to put up with the discomfort of travelling in Asia… (I have long held a similar opinion, but my notion of what might constitute too old may need to be updated…) I have also learned from his efficient solutions to solo travel. Among other things, he has two sets of clothes: one on, the other being washed – an easy way to avoid the fretting I had deciding what clothes to take. He carries a printout of Eurasia on which he has drawn the routes of his adventures to show to curious locals, especially those with which he has no language in common. He has a notebook computer and on it a database with masses of statistics on the countries he is visiting – thus somewhat cutting his umbilical to the Internet.

He and Karim, who has spent more than 20 years living in Germany, carried out ceaseless banter in German. When asked, Joachim would relay this to me in English. Karim would also act as an interpreter between me and Muchaba when necessary. In truth, Karim was constantly in conversation with someone – in fact, as far as I could see, just about everyone – facilitating with irrepressible spirit: a prime nexus in our social network.

One of the things that I have learned about travelling is the need for patience and acceptance. When travelling, even within the ‘developed’ world, transport arrangements often go wrong. For those who know me well, the notion of me patiently waiting to put the next tick on my to do list may seem a tad atypical, however it seems to me that the explanation is that, in one case I have the illusion of control, whereas in the other I clearly have none. This yielding to the inevitable is a lesson that it seems to me one we will all have to learn in the end.

Of course patience is harder for the young. On the train we had two examples of people making themselves unhappy by trying to force the world to their will.

The first was a young French Canadian who became angry with the waiter when he discovered that the dish that he had ordered was not available. He did not take into account either that the waiter and he were on opposite sides of a language (and probably culture) wall, nor that the poor man was labouring on his own to serve a large number of people whose requests he often did not understood. The young dude tried to draw me into sharing his outrage that the man should come and explain his failing to him personally.

The second was a young Swiss woman who was sunk in gloom and responded to our attempts to help her out with surly silence. Employing our ‘translation web’, we helped her order some food, only for her to push it about on a plate, decide that she wasn’t actually hungry, and then proceed to make a grumpy scene trying to get the same poor put upon waiter to somehow box the food so that she might take it to her compartment. When this wasn’t quite working out as she wanted, she petulantly stubbed out the cigarette (that she had insisted on lighting up in defiance of the no smoking sign – and just as we, sitting at the same table, were about to eat) and left…

Beneath cloudless blue skies, we sped (well, mostly ambled) through a landscape of immense plains ringed with hills, or sometimes snowy mountains. Looking upon these flat vastnesses, it became clear to me why it is that they have, for millennia, been dominated by horsemen of one kind or another. Rare stands of trees were mostly poplars. Scrubby undergrowth was all yellow straw – though our Iranian buddies assured us that, in spring, these same dusty plains are seas of green. Rivers sometimes cut gullies in dramatic windings. Sometimes a village forms a crust of roofs, and yet, though these vistas seem essentially unoccupied, much of the land seems under cultivation.

On the 20th of October, the train stopped near a hamlet and we were there for hours. Eventually we got off because someone told us there was a shop. I was waiting to buy some tangerines (that, with oranges, are called ‘portugals’ *grin* presumably for the same reason they are called ‘portuguese apples’ in Greece, and that turkeys are so named by the British – though they are more accurately called ‘perus’ by the Portuguese themselves) – anyway, I was trying to pay for these when the train horn went and people started running back. I got my ‘portugals’ and clambered back on board.

We were told that this delay was due to some track ahead needing repaired. So we arrived at Tatvan, on the shore of Lake Van, already two and a half hours late. As we waited for the ferry we walked about outside in the cold. There I talked to Tom, a young guy who had cycled from London to Istanbul, mostly camping wild, and who was anxious about the bike that he had not seen since he had handed it over to the train guard and that was presumably locked away in the baggage car.

We waited until it got dark. A rumour circulated that the delay was being caused by Kurdist separatists having put some obstruction across the track between us and the ferry. (Later I read a report that suggested this might be true). Finally, we made it onto the ferry; like most a gloomy warren of shapeless and ugly rooms. We attempted to hold together our ‘social order’ so that we might transplant it into the Iranian train that was hopefully waiting for us on the other side of the lake.

We made the crossing in pitch blackness at 9pm, when we should have been crossing at 3pm. Six hours later, bleary eyed, we stumbled off into some big shack that, thankfully, had power sockets with which Phones could be recharged and calls made home – the socket on our abandoned compartment hadn’t worked.

When the Iranian train arrived we boarded it to find it was some ancient German relic, incredibly cold and with no lights working in the dining car. In near darkness we ate some chicken and rice that indeed was, as Muchaba and Karim had claimed, much better than Turkish rice – indeed very much like basmati. When the lights came on the dining car was revealed in all its garish and tatty grandeur; heavy red curtains, bolted down swivelling chairs, plastic tables each with a little vase of plastic flowers: how I would imagine a cheap Blackpool boarding house to have looked in the 1960s.

By the way, I’m writing this in the darkness, on what we think is 7:30pm Iranian time, and as we are fairly speeding along between Miyaneh and Zanjan, with a supposed arrival time in Tehran at 4am on the 22nd; it should have been 8pm on the 21st. My body clock is all over the place, I’ve been sleeping when I can and eating erratically and so, if this is somewhat rambling, that’s likely to be at least partially the reason.

We had lurched off in our Iranian ghost train until we had to stop again, not that long after, at around 6am – my buddies and I had decided it was pointless to try to sleep – and we had to jump down off the train, and it was locked up behind us. In another large white hall we had to queue to have our passports checked. I felt lucky that we were near the head of the queue. When it was my turn the ‘stealth technology’ of my Portuguese passport seemed to be working too well: the Turkish official seemed disconcerted at having no idea where Portugal was… With my passport given back, I discovered that no one was allowed to return to the train until everyone was processed. I was desperate to get some sleep. At last, long after dawn, at least two hours later, we flooded back to the train and I clambered up to my bunk and was instantly asleep. Twice, while I was at the crux of compelling dreams, we were woken by Iranian offocials coming on board to check our passports. When we were left alone, I fell back into slumber as we were carried over the border into Iran.

When we rose, the landscape had become drier, though the same wide plains edged with hills dominated. Now and then we would run along the shore of some salt lake, a soft-edged blade gleaming silver.

At Tabriz Karim tried to persuade me to get off with him and go directly to Hamadan, but I held to my plan to visit there later and to carry on to Tehran. Disembarking to say goodbye to him and to watch Tom, joyously reunited with his bike (he is cycling down to the coast via Shiraz and Yazd – and undertaking that a local onlooker, recently returned from living in the USA, declared was going to be far more challenging than the 5000 kms he had traversed across Europe). Gazing around me, I wondered if I was catching my first intimations of the stark light for which Iran is famous, and that is supposed to lend a luminous intensity and depth to every colour. Certainly, framed by the modernist sweeping concrete canopy of the station, under the bluest sky, everything had a pure clarity.

As we trundled on I wrote everything you’ve read so far. feeling worn out. As Joachim and I ate our dinner, we mused at how, under the pressure of constant travel, time changes, erratic sleep and eating, what was left of our ‘society’ had broken apart. We retired early to our bunks and were woken at 3am to find that we were moving through the outskirts of Tehran. It was nearly an hour later before we arrived at the station. Joachim and I helped Mustaba off with his many bags – all of them incredibly heavy, filled with the catalogues and books that he brought back with him from his business trip to Turkey. We said goodbye to him and then, with some help from a Persian, Ako, I had become friendly with on the train, I eventually got to the hotel room that I had booked before leaving Scotland, and a very welcome bed.